In the late 1920s the world economy slumped into the Great Depression. In some areas of Sydney unemployment was 40 per cent. Many families had no incomes at all and could not pay their rent. Unemployment camps sprang up at various locations around Sydney including Happy Valley at La Perouse. Happy Valley was next to Anzac Parade behind Congwong Beach.

People often arrived with only the possessions they could carry. They would simply pick a spot and erect a hut with scrounged corrugated iron roofing, white washed hessian walls and earthen floors. They scrounged food from local Chinese market gardeners and local fishermen. The government provided one pint of milk per family per day.

In 1932 Happy Valley had a stable population of at least 330. While life at Happy Valley was hard, in other ways things weren’t so bad. One former resident recalled life as ‘happy, carefree, no rush and bustle, no money, no work, swimming all day on Congi Beach’. Another recalled that ‘we had freedom… even if it was the freedom to starve’.

The Aboriginal Mission was located opposite Happy Valley and the two communities enjoyed a good relationship. Extensive trade and interaction developed and many European- Aboriginal relationships formed resulting in many marriages and children.

In 1938 the NSW Golf Course, tired of having so many poor people living on its boundaries creating an eyesore for its wealthy patrons, pushed for evictions. The mayor of Randwick Alderman Bourke was also concerned about the Council’s image and the number of ‘illegitimate and half caste’ children being born at Happy Valley and lobbied the State Government to remove the camp. By 1939 all the residents were moved to more suitable housing and the huts were demolished.

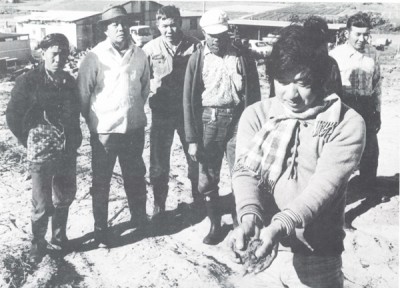

From the early 19th century the area abounded in market gardens supplying vegetables to the Sydney markets. These gardens had access to unlimited water from the Botany ponds and operated all year round. Until 1859 the gardens were owned and operated by Europeans. After the gold rushes of the 1850s, the Chinese gradually took over most of these gardens. Some Chinese also established laundries in the area. Traditionally the Chinese formed syndicates to lease land and work it to produce crops. This could be quite lucrative, generating up to 50 pounds a year for each partner in a good season.

By 1900 many of the gardens had been taken over by large merchants in Dixon and Hay streets in Sydney who paid low wages with food and board to sponsored labourers from China. The Immigration Restriction 1901 Act required the workers to live and work at the gardens and not move elsewhere without permits. The men lived in basic shacks made from corrugated iron. Food was cooked on open fires and they worked seven days a week. Most of them were single and Chinese prostitutes were known to visit the Matraville gardens once a week. The Chinese were suspected of smoking opium and gambling was a popular pastime, especially fan-tan and pakapu. European and Aboriginal locals also attended these games.

The Chinese gardeners, referred to as ‘Old Chow’ by the local community were respected as ‘men of honour’, but despite this the wider European community viewed them with suspicion. By the 1920s Chinese market gardens across New South Wales were under pressure from large scale industrial agriculture. Despite this the gardens at La Perouse remained viable throughout the 20th century and one still exists today.

Frog Hollow and Hill 60 were two other shanty towns near Yarra Bay. Many of the families living there were post World War 2 migrants from the Baltic countries, Germany, the Middle East and Aboriginal people from the South Coast. Most of these people worked full time in nearby suburbs. The camps were closed in the late 1950s and last shacks demolished in the early 1960s. Many descendents of these families now live in the Matraville and La Perouse areas.

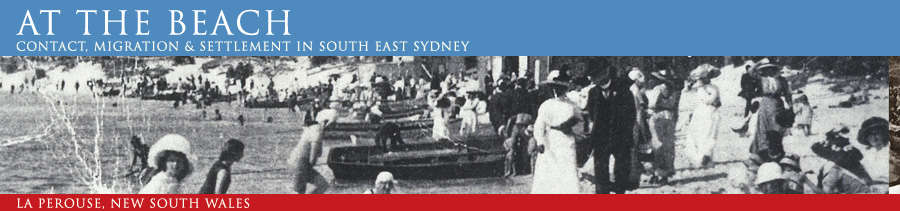

The electrification of the Sydney tram network began in 1895. By 1910 the electric line had been extended to La Perouse. The trams enabled factory workers to get away from the grime of the inner city. For the telegraph, hospital and the Salvation Army residents it provided access to Sydney.

- Russian Migrants Camp at Frog Hollow at La Perouse c.1950s Courtesy Randwick City Library

- Chinese Market Gardens at La Perouse c.1980s Courtesy Randwick City Library

- Unemployment Camp hut at Happy Valley c.1930s Courtesy State Library of NSW

- La Loop. The tram loop at La Perouse c.1920s. Lapérouse Museum Collection

- Chinese Market Gardens, Matraville c.1970s. Private Collection

- Happy Valley unemployed camp, La Perouse c.1932. Courtesy State Library of NSW